Throughout history, western images of the Islamic world have been subject to moulding and re-framing. ‘The orient’ is positioned either as the vibrant other: that strange and exotic world so unlike our own, or as an anchor, affirming the validity of established western cultures and ways of seeing. As Edward Said noted in the introduction to his book ‘Orientalism’:

“The Orient was almost a European invention, and had been since antiquity ‘a place of romance, exotic beings, haunting memories and landscapes, remarkable experiences. “

The rooting of this ‘oriental invention’ can be seen in the work of 18th century painter Jean-Etienne Liotard who, alongside his exquisite depictions of families (notably his own) and noble family life, documented the lives and fashions of the people he encountered during his travels in the east, and painted portraits of English society figures in ‘oriental’ dress.

Liotard lived a peripatetic existence. Born in the republic of Geneva, and having become not only a highly skilled draughtsman but an expert in beautifully detailed portraiture, he went on to seek fame and fortune throughout the capitals of Europe. His travels, moving from one commission to the next, took him from Paris, Rome, and London through to Amsterdam and Vienna. He also spent 4 years in Constantinople, where he travelled as a documentary artist, detailing the clothes and cultures of the people he encountered.

In his documentary work Liotard displayed a flair not only for brilliantly fine detail, but for an almost photographic ability to capture emotion and narrative.

Two exhibition works particularly stand out in this regard: one of a dwarf, depicted in middle aged and lost in thought, and the second of two Turkish musicians.

These drawings also show off Leotard’s skill with red and black pencil, a technique which carries over to his later ‘court portraits’ depicting European royalty. One of a young Marie-Antoinette is especially striking. But regardless of subject matter, this two colour approach lends a magical and highly stylised quality to his work: subjects appear as floating bright against a stark white background, details are drawn out with similar effect to Man Ray’s 20th century ‘Rayograph’ photographic experiments.

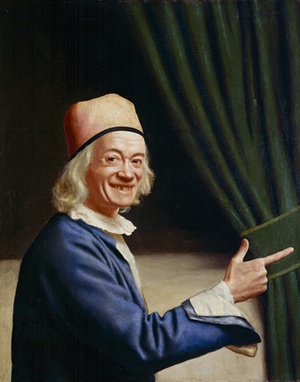

Humour, or at least playfulness, too, is a key feature of Liotard’s work. Self portraits depict him as smiling toothily towards the viewer, directing their attention away with pointed finger towards other works nearby.

There is a sense of comedy in the natural and candid way that he depicts his sitters. He allows them a wry grin and a knowing look, but he also refuses to beautify their flaws. The result is wall after wall of horrific women and puffily gout ridden men all painted with expert skill and attention. It becomes a constant delight to stumble now upon the portrait of a smirking woman, now on the startled and ruddy face of teenager on the verge of inheritance, and now upon the ageing, bloated aristocrat. It is not entirely clear to me how he came to get away with this trick. Perhaps was a much sought after signature, or perhaps (less likely) it was a secret in-joke only he was aware of. Either way, it is difficult to image the artist at work without a smile on his his face.

Comedy is also there in his ‘Oriental’ society portraits. Men appear slightly over-dressed, Women seem deliberately awkward in their foreign clothes.

This may be a mis-reading on my part but my feeling is that Liotard, when depicting the native people of the lands he travelled through, had a keener eye for the authenticity and reality of life than he allowed to trickle through into his European paintings. And I say this fully considering the theatrics at work in these portraits. Yes, the Turkish costume worn by the European girl or boy (often dressed in costumes Liotard himself has selected) speaks to a grander idea of their character and ambitions, but is there also the suggestion of an artist aware of the absurd and enjoying the playfulness of his situation? I like to think so.

Jean-Etienne Liotard at the Royal Academy of Art runs through to January 31, 2016

Related

You must log in to post a comment.